This has not been a typical December for me. I’ve had two friends die. In fact, I just returned from the funeral of one of them—my uncle Wallace E. Felldin (1920-2011). I knew him as “Uncle Wally.” It was my privilege to be able to speak briefly at his service, grieving with his family and celebrating his life.

He was, literally, a great uncle. When I think of him three words come to mind. He was kind. He was steady. And he was courageous. Let me comment on this last word—courageous.

A few years back, he visited our home in Colorado and I got him to tell my teenage boys about his military service during World War II, in Europe. Uncle Wally was part of that “greatest generation” that we sometimes hear about. In the war, he was an infantry leader serving with distinction in the 71st Infantry Division of the Army. He was a decorated hero—two battle stars, a Bronze star, etc..

One story he told us stood out above all. In 1944, he helped liberate a death camp run by the Nazis, filled with 18,000 Hungarian Jews. It was called Gunskirchen Lager, the central Nazi concentration camp in Austria.

His division did not know the camp existed. They literally “stumbled upon it.” As they got near, a strange smell warned them of the grim realities they were about to see. The large camp, surrounded by barbed wire, was filled with the intellectual class of Hungarian Jews—doctors, lawyers, and professors, whose lives were now reduced to an animal existence.

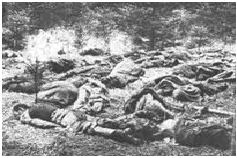

Words and photos cannot express the full horror and barbarity of it all. As he approached the camp he saw emaciated stragglers with skeleton-like frames, in stripped uniforms crying for “wasser” because they had no food or water for five days.

The camp was littered with the bodies of those the Nazis had starved and worked to death, as seen in the photo above.

The living were begging for food. Some who could walk, crowded around to touch the American soldiers to make sure they were real. They would kiss the hands of the embarrassed, nauseated Yanks. Some of the prisoners who could not walk, crawled toward them. Those who could not crawl, propped themselves up on elbows through their pain, and revealed eyes of gratitude and joy at the arrival of their liberators.

Uncle Wally and his unit reported back to call in immediate medical help. One of his fellow soldiers said, “the day I saw Gunskirchen Lager, I finally knew what I was fighting for and what the war was all about.”

My uncle did not talk much about this experience, until recent years, because some people are now claiming that the Holocaust never happened. This made my kind uncle fightin’ mad.

Uncle Wally’s story, of course, is deeply moving. But as we celebrated the life of this “death camp liberator,” who has now died, it struck me that this liberator himself needed to be liberated from death—as do we all. Each of us reading this, are in fact, “living in the land of the shadow of death.”

Year end magazines are filled with pages listing the famous people who died in 2011—Jackie Cooper, Jane Russell, Elizabeth Taylor, Steve Jobs, Betty Ford, Joe Frazier, Christopher Hitchens, Osama Bin Laden, Kim Jong Il, Mummar Qaddafi, Vaclav Havel, Duke Snider, Harmon Killebrew, John Stott, etc.. There are also the lesser-knowns, like the famine victims of Somalia, Tsunami victims in Japan, Middle Eastern Christians mowed down in the “Arab Spring,” and the relatively unknown people like my uncle.

Sitting in that funeral service, I was further reminded that the message of Christmas is actually about the arrival of another death camp liberator. Jesus’ arrival in the old carols of advent and Christmas is strikingly described.

He is the one whose coming will “put death’s dark shadow to flight.” Who, “from depths of hell Thy people save, and give(s) them victory over the grave (O Come O Come Emmanuel). He is the one who “comes to make his blessings flow far as the curse is found” (Joy to the World). Because of him it is said “Now ye need not fear the grave, Jesus Christ was born to save,” (Good Christian Men Rejoice) The classic carol, Hark the Herald Angels Sing, sums it up best of all, with the words—“Mild he lay his glory by, born that man no more may die, born to raise the sons of earth, born to give them second birth.”

In these songs of Christmas, Jesus is described as a kind of “death camp liberator.” How does he accomplish this? By his extraordinary coming (incarnation), his righteous life and sacrifice on the cross (atonement for our sins), his victory over death (resurrection), and promised return (second advent).

It is strange, isn’t it, that the strongest carols of the season say nothing about having a “holly jolly Christmas.” Instead they are ascriptions of praise to God for a glorious gospel that is as deep as the Hebrew Scriptures, yet as relevant as the grief of some of our Decembers.

This is good news for all of us. It is the faith that my uncle loved to sing about, and that the prophet Isaiah spoke about. “The people walking in darkness have seen a great light; on those living in the land of the shadow of death a light has dawned” (Isaiah 9.2, NIV).