There has been a lot made here of the fact that the Lausanne Congress at Cape Town 2010 meets on the 100th anniversary of the World Missionary Conference held in Edinburgh in 1910.

The Congress opened here last evening with the same opening hymn as the conference in Edinburgh 1910—with Crown Him With Many Crowns. Hearing 5,000 voices at this historic gathering from so many nations proclaim the supremacy of Jesus was deeply moving.

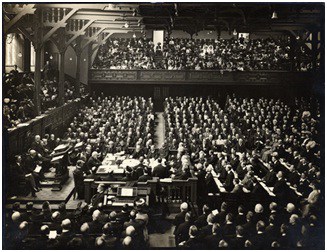

Edinburgh 1910

Back up to Edinburgh. The 1910 gathering took place at the end of the great European-American missionary thrust of the 19th century (the great century of missions) when new missions seeds were planted all over the world through pioneers like William Carey (India), Adoniram Judson (Burma), David Livingstone (Africa), Hudson Taylor (China) and many, many others.

Edinburgh was a huge (for that day) Protestant gathering of 1,200 delegates and 159 missionaries societies. It was inspired in part by the missions outreach of the 19th century, in part by the work of evangelist D.L. Moody, in part by the Student Volunteer Movement which he helped inspire, and in part by the vision of J.R. Mott (who was deeply influenced by Moody). Its watchword was “the evangelization of the world in this generation.” The conference represented the first time that Christian Protestant groups had joined together with the agenda of dividing up world missionary responsibilities and finishing the task of making Christ known everywhere.

Differences between Edinburgh and Cape Town

Of course there are a lot of differences between Edinburgh and Cape Town. Since Edinburgh, the advance of the gospel has been immense, especially in developing countries. The influence of worldwide evangelicalism, Bible translation, the spread of Pentecostalism, and even the Lausanne movement itself, have been used to spread the Christian faith to every nation in the world making Christianity the first truly global faith with over 2 billion followers.

If Edinburgh owed a lot of its motivational force to Moody, Cape Town and the entire Lausanne movement owe its motivational force to evangelist Billy Graham. Graham has not just led large evangelistic missions, but he organized multiple missionary congresses to strategize about how to bring Christ to the nations. One thinks of Montreux in 1960, Berlin in 1966, Lausanne in 1974, Amsterdam 1983, 1986, 2000, Lausanne II at Manila in 1989, and now Cape Town 2010.

While Edinburgh gave place on its program to churches from the third world, the dimensions of Christianity in 1910 were largely Western. Its vision and representation was not nearly as global as Cape Town 2010. Consider this: there were no delegates from Africa at Edinburgh.

When those delegates met in 1910, the majority of the world’s Christians lived in Europe and North America. The Christian faith was often referred to as a Western religion. In 2010, by contrast, most Christians now reside in the non-Western world. People speak of the “de-europeanization of Christianity.” There has been a seismic shift of the Christian faith from the north and the west to the south and the east. Perhaps that is why the Lausanne Committee chose Africa for this congress. Not only is the congress filled with many African Christians, it is in Africa.

The gathering in Edinburgh for missionary collaboration was focused on the exclusivity of Christ and his transforming gospel. Many different Protestants came together on this basis. This was a stunning demonstration of Protestant Christian unity, given the fractiousness of denominationalism. It was such a powerful moment, historians have said, that it marked the birth of the ecumenical movement—that even the formation of the World Council of Churches drew its inspiration from Edinburgh.

Unfortunately, the World Council these days is not known either for its commitment to evangelism or its unflinching witness to supremacy of Jesus. The corrosive elements of liberal theology have watered down its witness and its urgency to fulfill the Great Commission. That is one reason why the Lausanne movement came into being. It sought to restore what Protestants had lost, and what Edinburgh had affirmed. The Lausanne movement was after a gospel based ecumenism.

Finally, the issues before Edinburgh and Cape Town differ significantly. At the beginning of the 20th century, the most pressing issues facing the worldwide missionary outreach was the need to plant national church movements all over the globe, and to create an indigenous leadership that was not dependent upon European leadership. Looking back to 1910, we have to say that they succeeded and would have rejoiced to see something like Cape Town 2010.

And while a whole new set of missions challenges and opportunities face us here at the third Lausanne Congress—issues like secularization, the growth in new spiritualities, the aggressiveness of Islam, population explosion, globalization, urbanization, pluralism, relativism, and the digital revolution –that same Christ-centered, evangelistic urgency is still in place. The outstanding question is….will we be as faithful to Christ in our time as many of those delegates in Edinburgh were in theirs?