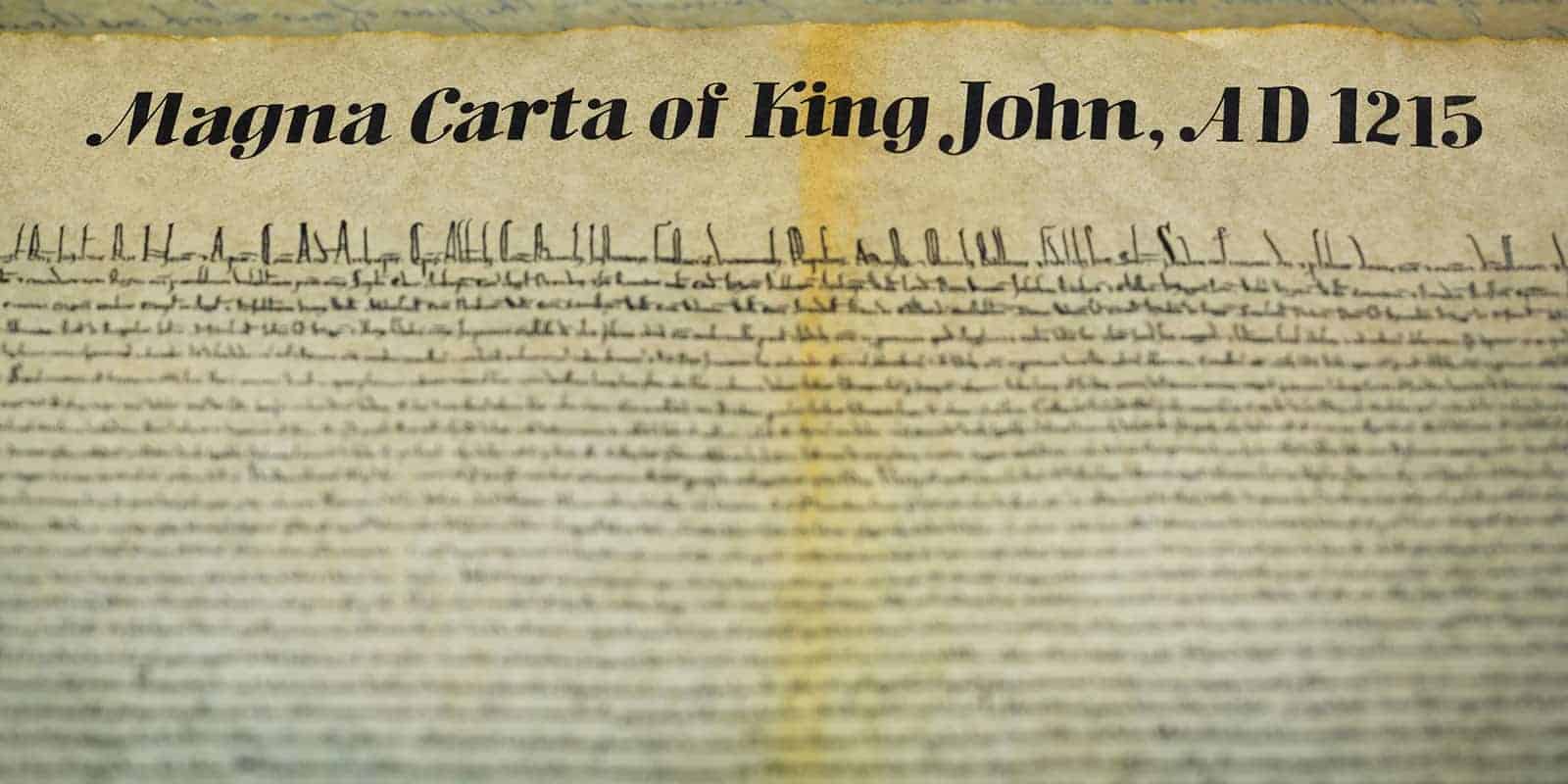

Why is the obvious so unobvious? This year we should all be celebrating the 800thanniversary of the Magna Carta. But sadly, the Christian influences on the formation of this great document are routinely ignored.

Magna Carta is Latin for Great Charter. This extremely important document has been called:

“the greatest constitutional document of all time, the foundation of the freedom of the individual against the arbitrary authority of the despot.”[1]

It helped establish the rule of law and constitutional government in the English speaking world.

It was signed on June 15, 1215 in England, when King John, pressured by church officials and English barons, reluctantly agreed to limit his powers. The king was no longer the law. He was under the law.

The Magna Carta not only affirmed the rule of law, but also listed 63 rights of the English people—including the sanctity of private property and due process.

Furthermore, the Magna Carta evidences early stirrings of representational government. If the king breaks the law and violates the rights of the English people, who should restrain him? Since he does not have absolute power, the answer is to be found in his accountability to the English people—which eventually came to mean, a representative assembly, i.e. a council of barons, parliament, etc..

Unfortunately, many who have been writing about the Magna Carta on this anniversary celebration omit four essential faith facts about the Magna Carta.

First, many forget the Christian framework of the Magna Carta. This is not simply a legal document with a secular framework. Just read its preface. It has an explicit Christian framework. It will not do to dismiss the opening words by saying, that these were just conventions of the time. They were, rather, common assumptions of the time.

The Magna Carta begins, “John, by the grace of God King of England.” It then says “Know that before God, for the health of our soul and those of our ancestors and heirs, to the honor of God, the exaltation of the holy church, and the better ordering of our kingdom.” That is the preface of the Magna Carta.

Second, many forget the primary advocacy of the church in writing the Magna Carta. Typical revisionism states that evil king John addressed this to his barons who rose in rebellion against him. Well, the document is addressed first to church leaders. Barons actually appear 5th on the list. The Magna Carta says it was written “at the advice of our reverend fathers,” and goes on to name numerous English church leaders first, including the influential Archbishop of Canterbury Stephen Langton. Langton helped mediate this dispute with the King and his subjects.

Third, many overlook the Biblical roots of the main idea of the Magna Carta. We hear a lot about this being “a document of unrivaled importance in the history of the West,” or that this was “the place where freedom was born,” or that this was “where the idea of law standing above the government first took contractual form.”[2]

Well, not so fast. In the Bible the idea of kings under the law is very clear. God is the sovereign ruler over all (Psalm 93). His kingdom is supreme. Kings rule under God. Read Psalm 2 and what it says about wise kings, foolish kings and the enthronement of God’s king.

The Magna Carta’s affirmation of the supremacy of law is based on a previous understanding of higher law, i.e. God’s law, which all men must obey. This earlier understanding can be seen in the Mosaic covenant of the Hebrew Scriptures. The Mosaic code, which included the Ten Commandments, was the real inspiration for such legal codes in the West, as is evidenced in the Magna Carta.

Read Deuteronomy 17.14 on God’s guidelines for Israel’s kings. A king was required to write for himself a copy of this law, then get his copy approved by the Levitical priests for accuracy, and then read it all the days of his life, “that he may learn to fear the Lord his God by keeping all the words of this law and doing them.” Talk about rule of law!

Turns out then that the Bible itself is “the greatest constitutional document of all time, the foundation of the freedom of the individual against the arbitrary authority of the despot.”

Finally, many ignore the first freedom established by the Magna Carta. In its list of 63 rights to be established, the first and the last listed are “that the English Church shall be free, and shall have its rights undiminished and its liberties unimpaired.” These, by the way, are the “great forgotten clauses of the Magna Carta.” Religious liberty is not only the first, but the first and the last among the liberties granted to all free men. This concern is echoed in the First Amendment of our own Bill of Rights.

Rule by law, rule under God, religious liberty: these are all theological ideas with deep Biblical roots. They are all affirmed in the Magna Carta.

As I said, this seems pretty obvious when you actually read the document. But then again, these days, the obvious is just not that obvious.

Christians should know about this, especially in an era when governments are tempted to forget that there are rules over rulers.

We can’t afford to forget about this and the massive role it has played in our own history.

[1] The words of Lord Denning, the most celebrated modern British jurist.

[2]Wall Street Journal, Section C1, May 30-31, 2015.